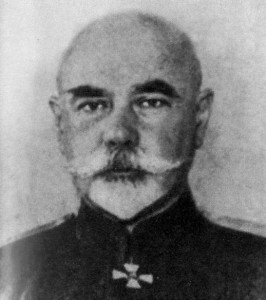

On December 16, 1872, the son of a one time serf, Anton Ivanovich Denikin was born in Szpetal Dolny. This small village in what is now Poland, was once a part of the Russian Empire. This unlikely leader was part of anti-communist movement during the Russian Civil War (Episode 71). He was to commit numerous atrocities, especially against the Jewish population. His push towards Moscow during the summer of 1919 almost toppled the Bolshevik’s but ultimately his army was defeated.

Anton Denikin was the son of a former serf, Ivan Efimovich Deniken who was forced into a 25 year tour of military service started in 1833. Eventually he would become an officer in 1856, retiring as a major. His father’s patriotic feelings towards the Tsar and the Russian Empire inspired Anton to go into the military himself. Another ideal that Denikin was to take from his father was his deep seated hatred of Jews.

Living in extreme poverty, Denikin began to take courses at Kiev Junker School in 1890. He graduated in 1892 and applied to the General Staff Academy in 1895. Unfortunately, Denikin could not meet the academic requirements in his first two years there. He continued to try and seemingly had made it only to find out that they changed the rules. He plead his case to the Grand Duke who made him an offer to enter that Denikin felt was an insult to his integrity.

Over the following years, Denikin continued to move up the ranks. In 1905, the Russo-Japanese War began and by now he was a colonel. By the time World War I began, he was now a major general. It was here that Denikin began to show his mettle.

While he had the cushy job of being named Quartermaster General Brusilov‘s 8th Army, he wanted to go to the front. He was given his wish when he joined the 4th Rifle Brigade. He was to serve brilliantly. During the Brusilov Offensive he was to help win the last Russian offensive during the war.

With the onset of the Russian Revolution in 1917, he joined the staff of Lavr Kornilov. Not liking what they saw with the Provisional Government, Denikin participated in the Kornilov Affair. He was arrested in September 1917 but escaped in October. Denikin joined Grand Duke Nicholas, Kornilov and other Russian officers to mount opposition to the Bolshevik’s.

When Kornilov was killed, Denikin took over as Commander-in-Chief. His mission was to capture Moscow and in the summer of 1919 he almost accomplished it. The city and the Bolshevik revolution was saved by a deal made between Leon Trotsky and Nestor Makhno‘s anarchist Black Army. Makhno would later be betrayed by the communists but he served his purpose.

While in retreat, Denikin’s army began its legacy of atrocities against the Jewish population. Over 100,000 were murdered in the pogroms. By now, international pressure and support forced Denikin to resign. He eventually fled to France but ended up in the United States in 1945, dying there in 1947. Initially buried in France, his remains were brought back to Russia in 2005 at the behest of his daughter. He is now buried at the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow.

2 replies on “Denikin – White Russian General”

Hi Mark

My husband and I are planning a trip to Russia in May, 2013. I was so excited to find your podcast, and am enjoying it so much! I am up to episode 86.

A while back, you referred to the 15 or so towns where Jews were allowed to live. Do you know the names of those towns? I have ancestors from Rypin, (now in Poland), and Polotsk, also spelled Polatsk, (now in Belarus). I know they came to NYC before 1908. I would like to know if either of those towns were among the ones where Jews were permitted to live, and any further information you might have on those towns.

Also, did you say you had not yet been to Russia? I wish you could guide us on our tour. We are going with “TRAVEL ALL RUSSIA”.

Again, thank you for educating us about Russia. I’m sure it will make our trip so much more worthwhile.

Paula

(an alumna of Brooklyn College)

Interesting article. During World War II, Denikin actually helped save Jews and was anti-Nazi. The Germans let him be because he was no threat to them.

The Russian Civil War was very complex. I read that there were White Army generals that forbade atrocities against Jews. For example, Admiral Kolchak published decrees, but they were ignored. Nestor Makhno, by the way, had a Jewish contingent among his army. He gave Jews arms so they could defend themselves.

Many generals and officers in the White Army were anti-Jewish. This was because many Bolshevik leaders such as Trotsky, were of Jewish origin. Also, Jews were perceived as the scapegoat for everyone’s problems, so they were attacked. This happened even when the general-in-chief made it clear that Jews were to be left alone. The hatred was too strong, and too many underlings disregarded the orders.

When the head of the army is far away from the front, and the subordinate generals are in charge, what do you think happens? Atrocities against civilians! So, like I said, there were generals that tried to prevent pogroms, but nothing came of their efforts. This is not to whitewash, but to state facts.

Admiral Kolchak said during his interrogation by the Reds that he was powerless against independent atamans. One soldier said, “Kolchak is Kolchak, a decree is a decree, and face is a face”. ( Kolchak Kolchakom, ukaz ukazom, a morda mordoi.”) The widely-held perception that all Jews were rich made them targets for pogroms and atrocities.

The problem with the White Guard was that they did not have an overall commander that would attack the Reds. Many fine generals, such as Kornilov, Alexeiev, Kappel, were killed early or died. This left generals that were not as capable. Also, the Whites did not have firm support from the Allies. Japan, U.S.A., Britain, France, all pursued their own interests. They wanted to use the civil war as an excuse to get important materiel from Russia. The Allies, except France, never really recognized the White movement.

If the Reds were one big red blanket, the Whites were a piecemeal blanket made up of different colors and pieces. Many White commanders feuded with each other for influence. Had they all united, perhaps they could have defeated the Red Army and communism.