If you’d like to support our podcast, please click on the link. https://www.buzzsprout.com/385372/support . Starting at $3 a month, any contribution will go a long way in helping to keep the podcast going.

Archive | Uncategorized RSS feed for this section

My Recommended Russian History Book List

On my Patreon Russian Rulers History podcast, I’ve been doing a few books reviews. Listener Alison, asked if I could post a list of the books. So, here they are.

The Siberians by Farley Mowat

In Siberia by Colin Thubron

My Sister’s Mother: A Memoir of War, Exile, and Stalin’s Siberia by Donna Slecka Urbikas

Gulag: A History by Anne Applebaum (highly recommended)

Memories of the Russian Court by Anna Viroubova

Russian Rebels: 1600 – 1800 by Paul Avrich

Women in Russian History: From the Tenth to the Twentieth Century by Natalia Pushkareva

Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia by Orlando Figes

Vladimir: The Russian Viking by Vladimir Volkof

Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales Ed. Serge A Zenkovsky

The Russian Civil War by Evan Mawdsley

Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy by Douglas Smith

For the fiction works:

Russka: A Novel of Russia by Edward Rutherford

Who is to Blame?: A Russian Riddle by Jane Marlow

How Did I Get Here? by Jane Marlow

The Third Series: The Beginning – The First Set of Books I Used

A History of Russia: Ninth Edition (I used the 7th) by Novholas V. Riasonovsky and Mark D. Steinberg

Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East by Martin Sixsmith

Russia: The Once and Future Empire from Pre-History to Putin by Philip Longfellow

The Romanovs: Ruling Russia 1613 – 1917 by Lindsey Hughes

Czars: Russia’s Rulers for Over One Thousand Years by James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci

As I add more book reviews, I’ll add them here. Over the coming weeks, I’ll also be adding links and pictures of the book covers.

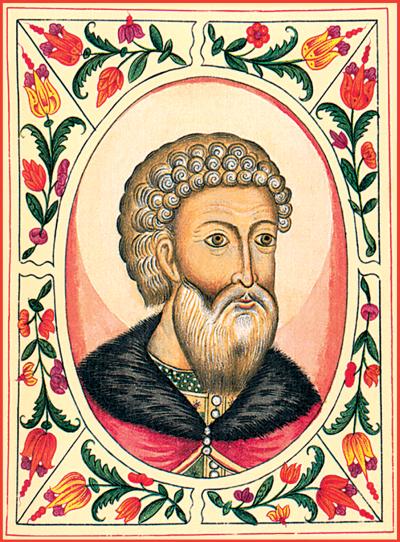

Ivan the Great – The Best Russian Ruler

Ivan the Great earned his sobriquet and makes his way on to my list as the best Russian ruler for a number of reasons. When I first put together my list, I had him behind both Alexander Nevsky and Peter I, but after careful review and research, he became my number one. The eldest son of Vasily II, he was the co-regent with his father to help solidify his family’s hold on to the throne. This was necessary as Russia was just leaving the period of their greatest civil war to date.

Because of the war, Ivan the Great felt a need to incorporate the previously independent city states into his realm as the Grand Prince of Moscow. Some of the principalities joined peacefully and willingly like Yaroslav and Rostov while others needed to be coaxed militarily. Novgorod and Tver were two of the states most resistant to Ivan’s pressure. After the battle at the Shelon River in 1471, Novgorod accepted Ivan the Great as their leader. Three years later, they tried to revolt again but were soundly defeated and their veche system (people’s assembly) was abolished.

It was after his total defeat of the Novgorodians that Ivan took the title of gosudar vseya Rusi or sovereign of all Russia. This was the first time that a Russian ruler had truly united his people. From here he also completely shed the yoke of the now weakened Golden Horde and stopped paying them any tribute. Khan Ahmad tried in 1472 and in 1480 to defeat Ivan the Great but failed both times. After the defeat of the Tatar’s at the Ugra River the yoke was finally overthrown.

What Ivan the Great also did was open up relations with countries to his west and south like Venice, Crimea, Hungary, Denmark and the Ottoman empire. He brought Italian architects to Moscow where the built the towers and walls of the Kremlin, something that remains to this day.

He also took on the idea of Moscow being the successor of Byzantium and of Rome when he married a Byzantine princess, Sophia Paleologue as his second wife. She bore Ivan the Great a son, who would become Vasily III. Ivan would go down in history as a shrewd politician and also earn the title of “gatherer of the Russian lands.”

Sakharov Released From Exile in Gorky

Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov was released from exile in the town of Gorky on December 19, 1986 by head of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev. He was one of the lead researchers in the Soviet development of nuclear weapons, a program known as the Third Idea. Sakharov was to be one of the leading advocates of improving Soviet human rights in the 60’s through the 1980’s.

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov was born on May 21, 1921 in Moscow to an educated couple, Dmitri Ivanovich Sakharov and Yekaterina Alekseyevna. His father was a physics teacher in a private school and later at the Second Moscow State University. Early on one could see that Sakharov was a brilliant student. In 1938, he entered Moscow State University to begin his studies later going to the Lebedev Physical Institute. There he honed his skills in physics where he received his PhD in 1947.

With the Cold War, Stalin pressured his scientists to catch up to the Americans with nuclear bombs of their own. Sakharov moved to the closed city of Sarov near Nizhny Novgorod (then the town of Gorky) to become an important part of the Soviet nuclear program. There he was part of the Third Idea, basically the building of thermonuclear weapons. In the coming years, he would feel little guilt about his part in creating the bombs as he thought that the threat reduced the risk of a third world war.

By the 1960’s, Sakharov began to see that the Soviet and American leaders were moving the world towards confrontation. He was worried about his role in any potential thermonuclear war. He pushed hard for the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in Moscow. It was the concept of anti-ballistic defense that created the true moral dillema that was to face Sakharov. In a letter to the Soviet leadership he wrote that they “take the Americans at their word for a bilateral rejection by the USA and the Soviet Union of the development of antiballistic missile defense.”

He wrote an essay in May of 1968 entitled, “Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom.” It gained international notoriety but the Soviet leadership was not pleased. He was banned from all military work and was by now closely watched by the KGB.

By the early 1970’s both he and author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn were targeted as dissidents and considered traitors. Constantly harassed he and his new wife, fellow dissident Yelana Bonner refused to back down. He won the Noble Peace Prize in 1975 but was banned by the government to leave the country and accept the award. On January 22, 1980 he was sent into internal exile in Gorky (now back to Nizhny Novgorod) for publicly protesting the war in Afghanistan.

He and his wife went on a number of hunger strikes to protest their treatment and to demand that Yelana be allowed to go to the United States for heart surgery. It was not until December 19, 1986 that Mikhail Gorbachev allowed him to return from exile. Three short years later, on December 14, 1989, Sakharov died of a heart attack at the age of 68. Around the world, there are now a number of awards named in his honor for people who fight for human rights. There is a physics award given by the American Physical Society “to recognize outstanding leadership and/or achievements of scientists in upholding human rights”.

Recent Comments